The Layman’s Guide To Reading Patent Claims: Can A Hippopotamus Infringe A Patent?

The Layman’s Guide To Reading Patent Claims: Can A Hippopotamus Infringe A Patent?

An Article in Schott, P.C.’s IP Law For Start-ups Series

By Stephen B. Schott

Patent claims are all-out assaults on the English language. It’s not bad enough that they are technical. It’s not challenging enough that passive use pervades technical writing. And it’s not brutal enough that the US Patent and Trademark Office has a pro-obfuscation rule about patent claims that requires them to be single run-on sentence monstrosities. No, it’s all of these and more.

But still, the essence of the patent is in its claims. So if you’re looking at a patent for almost any reason, you must read the claims. I will try to ease the pain of that exercise.

WHAT ARE THE CLAIMS?

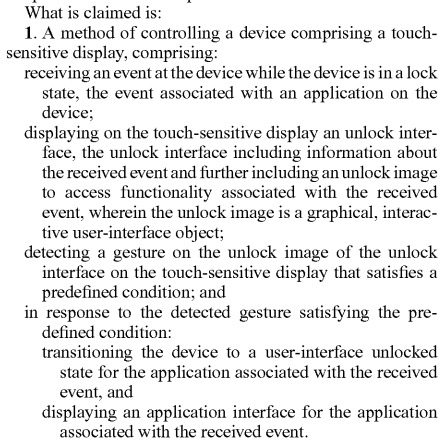

The claims are at the end of a patent. They often start with an introductory “I claim” or “We claim” followed by a series of numbered claims. An actual claim for Apple’s iPhone looks like this:

WHY ARE CLAIMS SO HARD TO READ?

A patent claim begins with a capital letter and often many semicolon-separated paragraphs later, ends with a period. Defenders of the rule requiring claims be a single sentence say that multi-paragraph long single sentences are clear. This argument is devoid of all logic: Retreating from the rules of grammar is no way to lead a charge towards clarity in writing.

On behalf of the US Patent and Trademark Office, for whom I am not authorized to speak in any capacity except that I, like you, am a taxpayer and their boss, apologize for patent claims’ opacity. Claims are hard to read.

WHAT DO THE CLAIMS HAVE TO DO WITH INFRINGING A PATENT?

A product or method infringes a patent if it falls within a patent claim’s scope. This is easier to understand in the context of an example.

Consider this fictional patent claim:

Claim 1. A chair comprising:

(1) 4 legs;

(2) a seat attached to at least one of the 4 legs; and

(3) a back attached to the seat, wherein the seat and the back attach to one another through a hinge.

The best way to look at this claim is to imagine that its words describe the boundaries to a property deed. But instead of “BEGINNING at a white oak on the E. bank of Sinking Creek, a corner to lots No. 8 & 10; thence S 53 E 20 P. 8 L. crossing said creek to three sourwoods; S 1.5 W 36 P,” the claim language might look something like this:

Seen this way, the claim language sets up the boundaries of what infringes the claim, and as a consequence, what the patent holder can prevent others from making, using, and selling. As shown in the example, a chair with 3 legs cannot infringe because the claim requires 4 legs. (Curiously, a five-legged chair might infringe the claim because a five-legged chair has 4 legs…plus one.) Similarly, a chair (stool) without a back would not be within the boundary, nor would a chair without a hinge between the seat and the back. None of these would infringe this claim.

But the chairs within the boundaries would infringe. One is a metal and fabric reclining chair and the other is a wood reclining chair. Despite the differences in these chairs, both have all of the claim elements and infringe claim 1.

You might ask “What are claim elements?” Claim elements or claim limitations are the words, usually broken into separate paragraphs or clauses, that make up the claim. Here, I made each of the claim elements a side in our “property.”

Note that the part of the claim “A chair comprising” is called the preamble. It may or may not serve as a boundary to the claim. Courts have said that the preamble is “necessary to give life, meaning, and vitality” to the claims. This is about as poetic as the patent law gets and we can see what the “life giving” might mean if we change the word “chair” to “something.”

As you can see, now the claim could cover a hippopotamus, which has 4 legs and a back attached though a hinge at the hip to a rather large seat.* Such a claim to “a something” would not likely ever issue in a patent but illustrates the importance of a preamble—it’s not something to totally ignore.

Returning to the claims, there may also be dependent claims in a patent. These are claims that add elements and further narrow a claim. For example, let’s add a claim 2 to our fictional patent.

Claim 2. The chair of claim 1, wherein the chair legs are wood.

Dependent claims usually have language like “The ___ of claim __” or “The _____ according to claim ___.” What this means is that the dependent claim includes all of the elements of the claim it refers to plus whatever is in the dependent claim. In our example, we would say that claim 2 depends from claim 1.

In determining the scope of claim 2, we might redraw the patent property boundaries like this:

This shows how the metal-legged chair that was within the scope of claim 1 is now outside the scope of claim 2 because claim 2 requires wooden legs.

This isn’t the complete infringement analysis process. What I just discussed is the second step in it: Comparing the claim language to an accused product. The first step is interpreting the claim language. It turns out that statements made in the patent description and during the patent proceedings in the US Patent and Trademark Office, drawings, and other factors help inform what the claim language means. Interpreting claim language is a topic for a more advanced article.

THAT’S GREAT. HOW CAN I TELL IF THE CLAIM IS VALID?

There are a lot of technical reasons a claim might be invalid. But one way that a claim might be invalid is if it lacks novelty or if it is obvious. Going back to our property lines, a claim would lack novelty if at the time of the application’s filing, one of the chairs within the property boundary already existed. Said in patent parlance, a claim lacks novelty if a prior art reference teaches or shows every claim element.

A patent claim may also be invalid if it obvious. A defendant may show this by taking one reference (a four legged chair with no back) and combining it with another reference (a three legged chair with a hinged back) to create a combination that shows all of the claim elements.

An infringement or invalidity study is a complicated analysis. If you are concerned that your product infringes a patent, or if you believe a patent asserted against you is invalid, you should find an experienced patent attorney and secure their opinion.

If you want more articles like this, please sign up for updates as they happen or our monthly newsletter.

* Alas, the hippopotamus cannot infringe the patent claim because it is a naturally-occurring composition of matter.